Tech Ban Defensive Tactics: Can China Protect Their AI Industry?

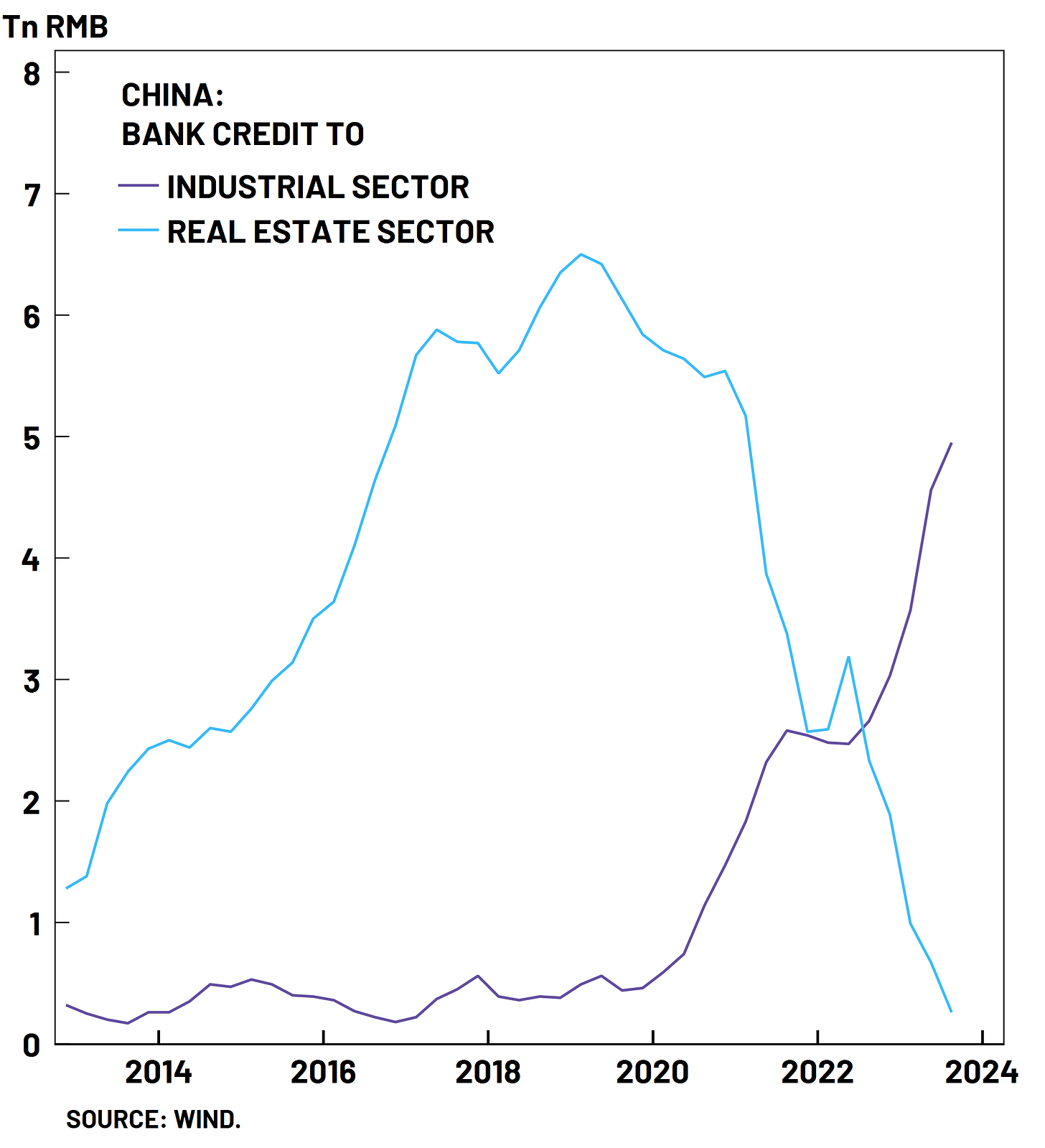

China has tactical opportunities to shield their AI industry and continue progress However, the Chinese AI start-up ecosystem is suffering severe downturn and lags the US by a long distance.

The U.S. has recently imposed additional restrictions on AI chips and chip-making equipment, underscoring its determination to safeguard its leadership in AI technology. By essentially classifying advanced AI chips under arms export controls, the U.S. signals its view that maintaining an edge in AI is crucial. In this piece, we revisit some of our earlier research on the impact of the chip sanctions on China’s AI industry and analyze how China can adapt to the new regime of sanctions. In this discussion we focus on tactical options, without much review of the overarching strategic context. In the next paper, we will look at strategy.

Read our previous piece for a background on the controls:

Key Takeaways

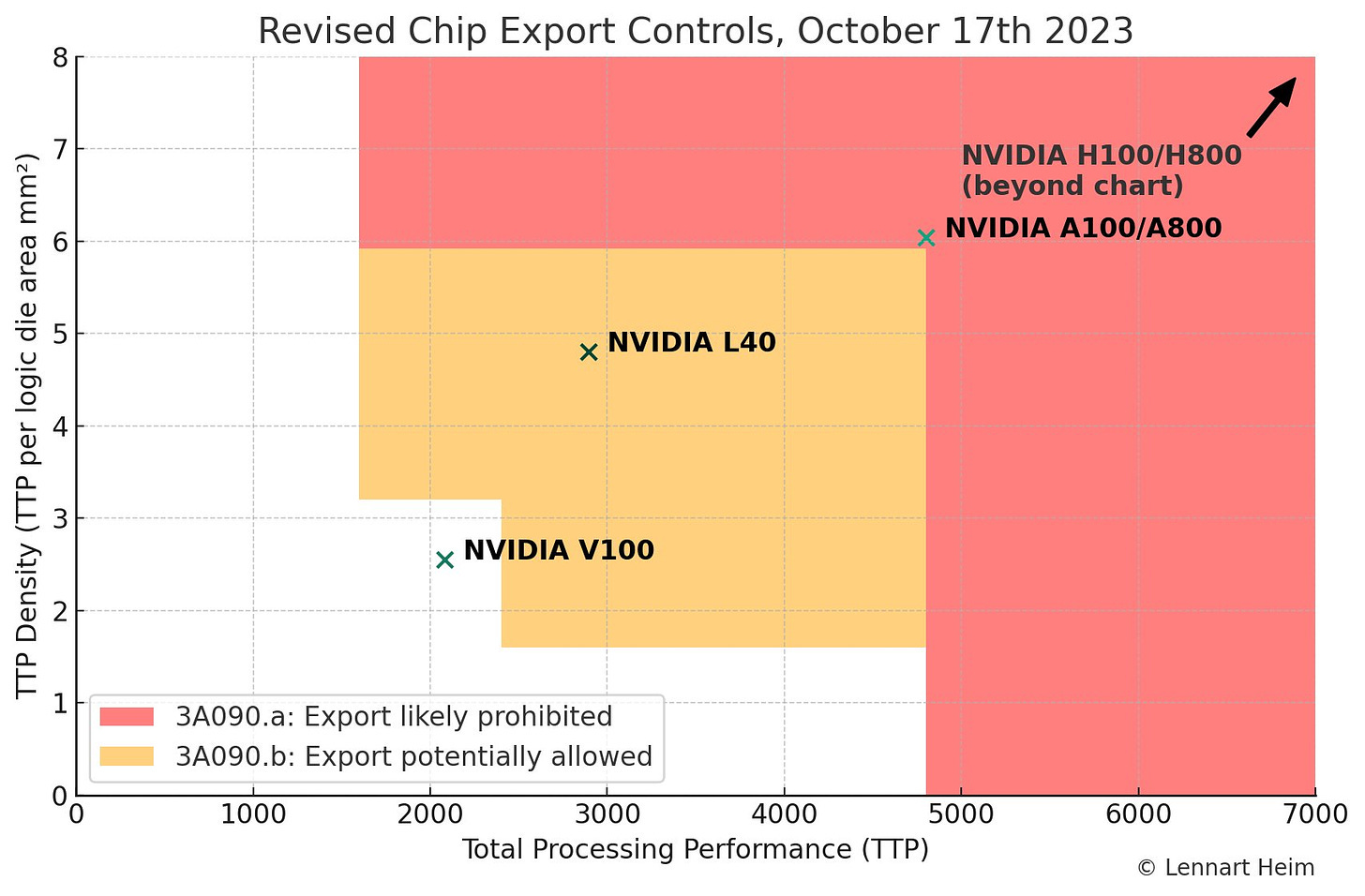

NVidia A800/H800 Can’t be Sold to China Anymore: NVidia responded to the October 2022 ban by developing AI chips tailored for the Chinese market, the A800 and the H800, ensuring it remained just beneath the performance benchmarks. The new October 2023 restrictions closes this loophole, which blocks the NVidias A800 and H800. Chinese companies will be limited to much older chips, like NVidias V100, which was released in 2017 based on 12nm, and is many times less powerful that the A100 and H100.

NVidia Probably Won’t be Designing Around these Sanctions: While companies like Nvidia may contemplate introducing China-specific chip designs to maneuver around these regulations, the constraints imposed by the performance density rule make this almost impossible. However, if there is a way, NVidia will find it.

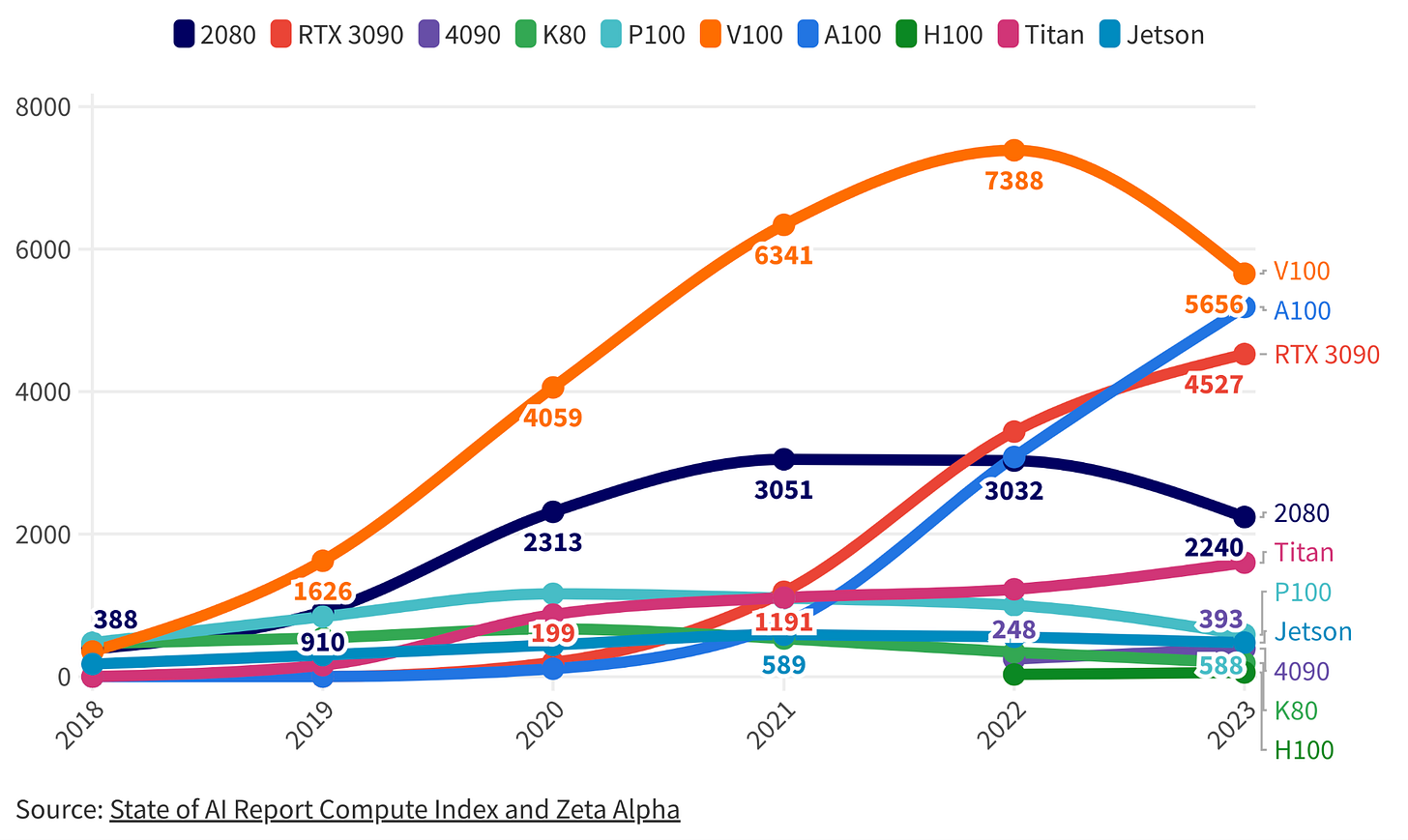

Diverse Chip Combinations as a Solution: Chinese companies are merging three or four older-generation chips to emulate the capability of Nvidia's top processors. This approach requires AI systems, where NVidia has a huge multi-year lead on Chinese counterparts. However, given that NVIDIA chips possess an impressive lifespan – with a 5-year span from launch to peak popularity – Chinese enterprises maintain a good lifetime with their acquired A800 and H800 models.

Continued Progress Required Systems, Algorithms AND Hardware: While China may face challenges in developing competitive hardware, algorithms offers a pathway for development. However the big behemoth in the room is model size, which has increased by 17.6x each year for the last decade. Expanding AI model sizes put extraordinary pressure on 1) AI Hardware Performance, 2) AI Model Efficiency and 3) AI Infrastructure Scaling. Losing out on any of those fronts will kill an AI company’s competitive edge. For growth, software alone isn’t enough.

Chinese GPU designers will turn to local fabs: In the immediate future, Huawei appears to be the front-runner for local chip designs. Huawei has successfully produced a 7nm ASIC using SMIC. The 2019 Ascend 910 from Huawei already surpasses existing regulations, implying that a homegrown successor would likely outpace anything Nvidia is permitted to deliver to China. While the immediate outlook appears bleak for sanctions Chinese GPU companies, with the unwavering support from the Chinese state, these firms have the opportunity to pivot to domestic production alternatives.

Chinese Hyperscalers can access chips unlike start-ups: Well-established corporations like Alibaba or Tencent have the financial muscle and strategic agility to navigate these challenges. The scarcity of GPUs benefits the major cloud players on a relative basis while posing challenges for smaller firms who lack the scale and inventory to access hardware. This is in contrast to the U.S., where startups have easy access to the necessary hardware, fostering innovation and the development of new models.

National priorities and lack of hardware will thin out Chinese AI: As the nation grapples with limited AI chip resources, priority will undoubtedly be given to projects of national significance. Those deemed non-essential might find themselves sidelined or abandoned altogether. This stringent resource allocation, encompassing both financial investments and compute power, underscores the necessity for China to adopt an extremely streamlined approach to resource management. While such a strategy may keep them in the race, it concurrently risks thinning the depth and diversity of their AI ecosystem.

Chinese AI startups face a glaring capital crunch: Instead of fueling AI innovations, the bulk of China's tech risk capital is channeled into chip development, leaving the AI sector to be largely dominated by hyperscalers. This landscape presents an almost absurd risk for venture capitalists. The majority of funds raised by AI startups in are immediately consumed by the pressing need to purchase GPUs and critical infrastructure. Without these essential components, startups can't even take their first steps. AI funding in China soared to a remarkable $30B in 2018 but has witnessed a precipitous decline since, with projections standing at a mere $2B for 2023. Meanwhile, the U.S. AI startup ecosystem thrives, consistently securing over $30B annually since 2018 and reaching an astounding peak of $66B in 2021. The gap is widening.

Chip Choke Trumps the Credit Crunch

Beijing continues to prioritize investments in its semiconductor industry amidst the technological rivalry with the U.S., rather than unleashing broad economic stimulus measures. This prioritization demonstrates the willingness to safeguard economic security, possibly at the expense of short-term economic growth.

China's economic revival remains sluggish. While China unleashed a 4 trillion yuan stimulus post the 2008 financial crisis, there are no signs indicate a bazooka approach now, with local governmental debts and slowing tax revenue growth being barriers. The country's tax revenue was 13.8% of its GDP in the previous year, a decline of nearly 5% since 2014.

On Tuesday, 24th October, the government significantly increased its headline deficit, marking the largest in three decades, and introduced a sovereign debt package deviating from its conventional fiscal support model. This one trillion yuan ($137 billion) boost marks a departure from the 3% cap on the deficit-to-GDP ratio. Notably, instead of the massive "bazooka" stimulus seen in previous downturns, the current budget increase, equivalent to approximately 0.8% of GDP, remains modest. The emphasis of the stimulus remains on construction, specifically targeting post-flood recovery and disaster prevention, aligning with Xi's dual objectives of economic growth and security.

Amid budgetary limitations, Beijing emphasizes sectors like domestic semiconductors and electric vehicle production, preparing another $40 billion dollar semiconductor fund. Recently, Beijing declared expanded tax benefits for semiconductor and machine tool sectors, allowing a 120% tax deduction on R&D expenses for five years. We remind readers of our assessment that for China to develop an indigenous supply chain at current 5nm technology levels could take to the end of the decade.

Beijing's prioritization of chip investments ($40B on one technology) compared to broader stimuli ($137B across many sectors) underscores its significance in the eyes of Chinese leadership. Given the transformative potential of AI in bolstering productivity and military power, this could be decisive for China's long-term trajectory. In the absence of foreign cutting-edge chips, a looming question is whether China's AI evolution can remain competitive, ensuring significant productivity and military enhancements even when reliant on dated chip technology.

Defensive Tech Tactics

Under tech restrictions, Chinese companies will need to innovate and effectively mix AI chips, run efficient AI programs on less efficient supercomputers, and design good enough domestic GPU accelerators. Consequently, the current restrictions on AI chips and chip manufacturing technology may mean that Beijing has to press pause on it’s global technology leadership bid, but may not pose an existential threat.

“I definitely think it’s true that the interventions that have been taken so far on the export controls, are likely to have a seismic impact on China's ability to train the next generation of frontier models. Fundamentally all training depends on these chips, Nvidia GPUs and each generation is way more powerful than the previous.” Mustafa Suleyman, founder of DeepMind

Tactic 1: Mix and Match the Foreign Chips

U.S. sanctions have prompted Chinese tech firms to hasten research for advanced artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities without depending on American semiconductors. An analysis by the Wall Street Journal indicates that companies, including Huawei, Baidu, and Alibaba, are exploring methods to maximize the performance of their existing chips without relying solely on the newest models. Additionally, they are experimenting with combining various chip types to diversify their hardware dependence.

Strategic Resource Allocation in Chinese Tech Giants

After February this year, companies such as ByteDance, which already have significant cloud computing stakes, increased their orders with NVIDIA. ByteDance, for example, placed orders worth over $1 billion on GPUs. Meanwhile, firms that had already stocked up on A100s, like Alibaba and Baidu, are now limiting the use of these advanced foreign chips, reserving them for more intensive computational tasks. Baidu has even paused using its A100s for departments like its self-driving unit to allocate them for the development of its ChatGPT equivalent, Ernie Bot.

NVidia A800/H800 Can’t be Sold to China Anymore

The US banned leading edge NVidia chips from being sold to China in October 2022. However, driven by the allure of short-term profits, NVidia responded to the BIS constraints strategically. The tech giant developed AI chips tailored for the Chinese market, the A800 and the H800, ensuring it remained just beneath the performance benchmarks set by the U.S. Commerce Department. This crafty move allowed the A800/H800 to substitute the A100/H100 in data centers, bypassing the newly imposed restrictions with comparable performance for AI training workloads.

The new restrictions with the “Total Processing Performance” (TPP) and “TPP Density” metrics solves this loophole, which blocks the NVidias A800 and H800. It also means a range of other chips from Intel and AMD are banned too, see SemiAnalysis table below for examples of chips that are allowed and banned. Chinese companies will be limited to much older chips, like NVidias V100, which was released in 2017 based on 12nm, and is many times less powerful that the A100 and H100.

NVidia Probably Won’t be Designing Around these Sanctions

The debate surrounding the concept of "performance density" in the context of chip export controls is intricate. Recent suggestions have surfaced, proposing the expansion of the processor area as a means to dilute performance density, thus potentially bypassing regulations. However, experts have countered this line of thought, arguing that such design modifications would severely compromise chip performance, effectively nullifying the intent behind such design alterations. Specifically, while companies like Nvidia may contemplate introducing China-specific chip designs to maneuver around these regulations, the constraints imposed by the performance density rule make this almost impossible. Adopting strategies such as incorporating blank silicon to artificially inflate the chip's size won't pass muster, as regulations account for such tactics. Essentially, any hardware adhering to these stipulations won't be efficient enough to run large transformers, rendering the design workaround futile. This highlights the stringent nature of the "performance density" criteria, ensuring chip manufacturers can't sidestep regulations without sacrificing the chip's core functionality and efficiency.

Diverse Chip Combinations as a Solution

Chinese companies are now merging three or four older-generation chips to emulate the capability of Nvidia's top processors. This methodology, however, can be expensive and slow. This scenario has motivated some enterprises to fast-track the creation of techniques for training expansive AI models across an assortment of chips. Giants like Alibaba, Baidu, and Huawei have been documented trying various combinations of A100s, older Nvidia chips, and Huawei Ascends to optimize performance while managing costs.

AI systems, where NVidia has a huge multi-year lead on Chinese counterparts, requires engineering out a diverse set of problems. AI accelerator systems address challenges like the "memory wall problem", the gap between computational speed and memory accessibility. Distributing tasks across multiple accelerators presents its own set of challenges, including communication limitations. Addressing these challenges might require multiple years for Chinese companies to develop systems that provide a combination of more strategic deployment methods, and a rethinking of AI accelerator designs to balance computational and memory needs. Or alternative implementations of AI models entirely.

Given that NVIDIA chips possess an impressive lifespan – with a 5-year span from launch to peak popularity – Chinese enterprises maintain a good lifetime with their acquired A800 and H800 models.

In 2023, all eyes were on NVIDIA’s new H100 GPU, the more powerful successor to the A100. While H100 clusters are being built (not without hiccups), researchers are relying on the V100, A100 and RTX 3090. It is quite remarkably how much competitive longevity NVIDIA products have: the V100, released in 2017, is still the most commonly used chip in AI research. This suggests A100s, released in 2020, could peak in 2026 when the V100 is likely to hit its trough. The new H100 could therefore be with us until well into the next decade! State of AI Report

Tactic 2: More Efficient AI Models

Innovation isn't always about sheer power—it's about using resources effectively. While the U.S. often emphasizes maximizing resources, other nations have thrived by focusing on efficiency. History provides ample evidence of this dynamic.

The Japanese Case Study: Vehicles and Appliances

During the latter half of the 20th century, the Japanese auto industry disrupted the global market with a unique proposition: highly efficient, reliable, and affordable vehicles. Instead of the gas-guzzling behemoths popular in the U.S. where fuel was cheap, brands like Toyota and Honda introduced models that were fuel-efficient and required fewer repairs. Similarly, in the realm of home appliances, Japanese companies like Daikin took the lead in air conditioner innovation. While American manufacturers focused on raw cooling power due to cheap electricity, Japanese models were designed with energy efficiency and compactness in mind. This strategic emphasis on efficiency propelled Japanese brands to the forefront of the global market, with their products being synonymous with reliability and value.

The Algorithmic Era and AI's Evolution

Algorithms are sets of rules driving operations, allowing AI systems to utilize computational resources to analyze data. While processing more data is one method, there's a trend of refining these algorithms to achieve results with fewer resources. One study showed that “every nine months, the introduction of better algorithms contributes the equivalent of a doubling of computation budgets”. When compared with Moore's Law, where computer power doubles every two years, it's evident that efficient algorithms will contribute more to the rate of change of AI than raw compute power. However, multiplied out over the long term the world leaders will develop both hardware and software.

Currently, the industry overfits to exploring AI techniques that work well on existing chips, i.e Nvidia GPUs/Google TPUs running variants of transformers. With the AI Accelerator sanctions on China, one interesting result might be that China forks silicon and explores a different idea-space in AI techniques than the rest of the world. After all, the brain and the signals propagating on it look nothing like our current hardware/software architectures either.

China will invest heavily in compute in memory, neuromorphic computing, or some other analog approach. Currently, none of these approaches show promise in transformers or diffusion models, but that says nothing of new model architectures. Semianalysis, Wafer Wars

Continued Progress Required Algorithms AND Hardware

Understanding this is important when examining the trajectory of Chinese firms in the AI sector. While they may face challenges in developing competitive hardware, the nature of algorithms—which can be replicated—offers a pathway for development. However, model size throws a spanner in these gears. To summarize the pace of development:

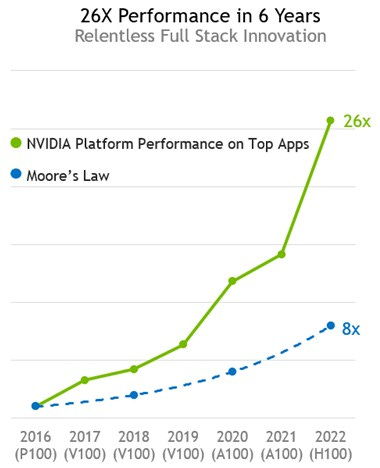

Moore’s Law: transistor density 2x every 2 years.

Around every year, AI algorithms become 2x more efficient to run.

AI accelerator systems get about 1.8x better performance every year.

Taking the AI accelerator improvements (which already include Moores law) and AI algorithm efficiency gets us 3.6x improvement every year. However the big behemoth in the room is model size, which has increased by 17.6x each year for the last decade. So subtracting out efficiency improvements means that one would have to 14x chip capacity to keep pace with model development. Now, that’s not entirely true because companies can reallocate resources to focus on major projects but the point is that expanding AI models put extraordinary pressure on 1) AI Hardware Performance, 2) AI Model Efficiency and 3) AI Infrastructure Scaling. Losing out on any of those fronts will kill an AI companies competitive edge.

For continued growth, China needs to invest in algorithm development and consider new designs for AI accelerators, rooted in their own chip innovations. Software alone won't be enough.

Tactic 3: Design and Produce Chips Domestically

“Huawei is committed to building a solid computing power base in China – and a second option for the world,” Meng Wanzhou, Huawei CFO

Local Designs Better than Available Foreign Chips: Ramping Up Local Production

Despite the international restrictions on AI chips, China's semiconductor industry is showing resilience and innovation. A notable highlight is Baidu AI Cloud's unveiling of the "Kunlun" 2nd generation 7-nm general GPU. Kunlun's 2nd gen chip has also successfully replaced foreign-made chips in quality inspections, slashing costs by up to 65%. Furthermore, the R&D for the 3rd generation is underway, with mass production targeted for 2024, aiming to cater to the domestic high-end demand.

The short-term path forward is with Huawei. Huawei has taped out a 7nm ASIC on SMIC’s N+2 process node. It is a successor to the Ascend 910 that Huawei launched back in 2019. We hear this chip utilizes chiplets and contains HBM. China stockpiled millions of units of HBM from SK Hynix and Samsung this year. It is not clear where these are being deployed, because there are no high-volume chips domestically produced in China that can utilize these HBM stacks. The only logical conclusion is that these were imported for Huawei’s upcoming chip.

Hawuei’s Ascend 910 from 2019 already breaks the current regulations, so a domestically produced successor would also beat anything Nvidia can legally ship into the country. While some would argue SMIC is not capable, the fact is that their old 14nm was already used to make an exascale supercomputer. The new N+2 node (7nm) is approaching 20,000 WPM of capacity, which is enough for millions of accelerators at even 50% yields. Furthermore, China is rapidly approaching capabilities of manufacturing HBM domestically at CXMT, but more on that in a bit. Semianalysis, Wafer Wars

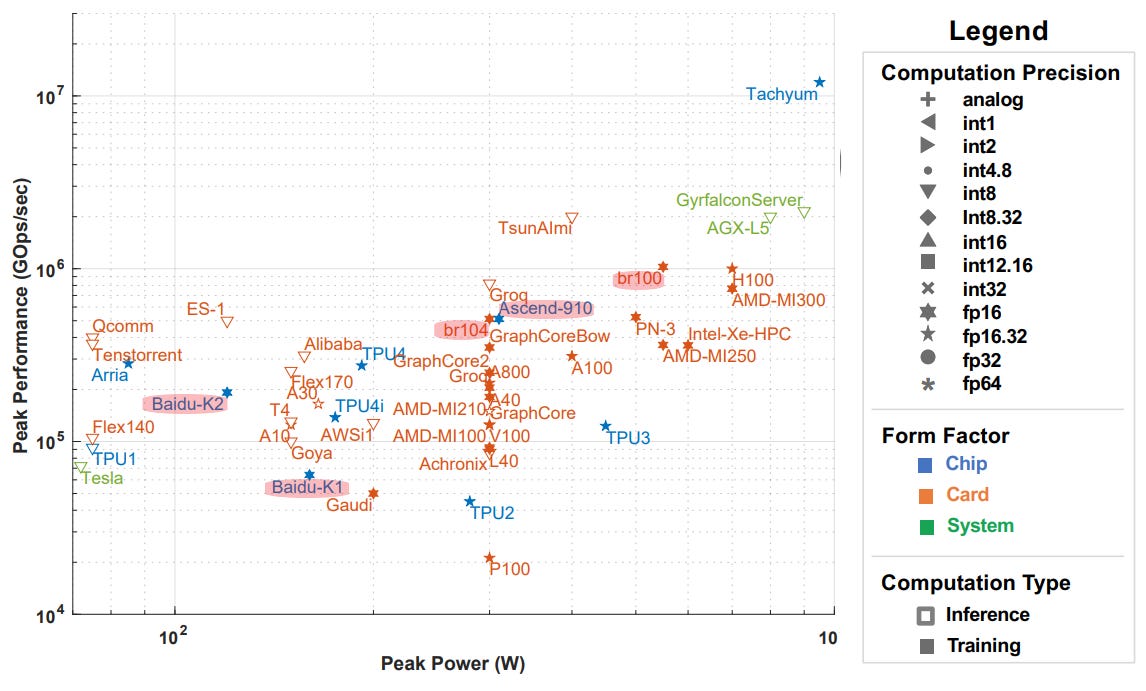

Comparative Analysis with Nvidia

While it's heartening for Chinese semiconductor manufacturers, it's essential to maintain a comparative perspective. Top Chinese AI chips are broadly analogous to Nvidia chips that were state-of-the-art five years ago. Certain benchmarks have demonstrated Huawei's Ascend 910 matching the performance of Nvidia's V100 in AI workloads. Yet, Nvidia's H100, which China currently cannot access, is a powerhouse, outperforming the older V100 by over 13-fold.

Effect of Entity Listing Biren and Moore

Recent U.S. trade sanctions have put two of China's leading tech companies, Biren Technology and Moore Threads, under immense pressure. These companies, both having the potential to challenge tech giants Nvidia and Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) in the field of graphics processors, now face significant hurdles in their race to the top. Notably, Huawei's Ascend range and Biren's BR100 chips have emerged as promising contenders.

U.S. Sanctions and their Impact

The severity of the U.S. sanctions has led to strong reactions from both Biren Technology and Moore Threads. Biren has called for a re-examination of the U.S. government's decision, while Moore Threads emphasizes its adherence to relevant laws and regulations.

But the new sanctions aren't the first challenges Biren has faced. In October 2022, TSMC, suspended shipments for Biren. Given that Biren designs processors specifically for AI and high-performance computing (HPC) applications, this halt was a significant blow. Mere weeks after the suspension from TSMC, reports emerged suggesting that Biren Technology was preparing to lay off a third of its workforce.

The Silver Lining: Domestic Innovations and Strategic Moves

While the immediate outlook appears bleak for Biren and its counterparts, there's a potential silver lining. With the unwavering support from the Chinese state, these firms have the opportunity to pivot to domestic alternatives. SMIC, with its 14/7nm capabilities, stands out as a viable option for GPU fabrication. Turning to SMIC not only provides an avenue to sidestep current supply chain challenges but also has the added benefit of bolstering domestic Chinese semiconductor capabilities. As these companies transition towards utilizing local fabs, TSMC might witness a shift in demand. This move is not just about surviving current challenges but could mark a strategic realignment, bolstering China's domestic tech industry and reducing its reliance on external players.

China's Mitigation: Scale and Centralization

The centralized and large-scale approach China adopts in many of its technological endeavors could be its trump card:

“On August 30, Alibaba Cloud announced the official launch of its Zhangbei Super Intelligent Computing Center, with a total construction scale of 12 EFLOPS (12 quintillion floating-point operations per second) AI computing power, which will surpass Google’s 9 EFLOPS and Tesla’s 1.8 EFLOPS. The new construction is now the largest intelligent computing center in the world able to provide powerful intelligent computing services for AI large model training, automated driving, spatial geography and other AI exploration applications.”

However Google is already planning a supercomputer that is double the size of Alibaba’s and announced in May a 26 EFLOP supercomputer made with NVidias H100’s or Cerebras’ (US) planned project of 36 EFLOPS in the UAE. Chinese companies still lack the scale of compute of their American counterparts.

Gaping Weakness, Early Stage Start ups

While Chinese tech giants like Alibaba have the resources to maintain a somewhat competitive scale, budding AI startups in China will struggle to find their footing amidst these dynamics. Well-established corporations like Alibaba or Tencent have the financial muscle and strategic agility to navigate such challenges. In China, the scarcity of GPUs benefits the major cloud players on a relative basis while posing challenges for smaller firms who lack the scale and inventory to access hardware. This is in contrast to the U.S., where startups have easy access to the necessary hardware, fostering innovation and the development of new models.

Furthermore, as the nation grapples with limited AI chip resources, priority will undoubtedly be given to projects of national significance. Those deemed non-essential might find themselves sidelined or abandoned altogether. This stringent resource allocation, encompassing both financial investments and compute power, underscores the necessity for China to adopt an extremely streamlined approach to resource management. While such a strategy may keep them in the race, it concurrently risks thinning the depth and diversity of their AI ecosystem. In comparison, the US and its allies, with their expansive technological ecosystems, benefit from a more holistic and layered approach. This multifaceted ecosystem not only aids in fostering innovation but also offers a robust safety net against potential technological or geopolitical shocks.

Chinese AI startups face a glaring capital crunch, painting a stark contrast with their American counterparts. Instead of fueling AI innovations, the bulk of China's tech risk capital is channeled into chip development, leaving the AI sector largely to be dominated by hyperscalers. This landscape presents an almost absurd risk for venture capitalists. The majority of funds raised by AI startups in China are immediately consumed by the pressing need to purchase GPUs and critical infrastructure. Without these essential components, startups can't even take their first steps. In a telling trend, AI funding in China soared to a remarkable $30B in 2018 but has witnessed a precipitous decline since, with projections standing at a mere $2B for 2023. Meanwhile, the U.S. AI startup ecosystem thrives, consistently securing over $30B annually since 2018 and reaching an astounding peak of $66B in 2021. The gap is widening, and it's crucial to ponder its implications for the global AI landscape.

Coming for Cloud

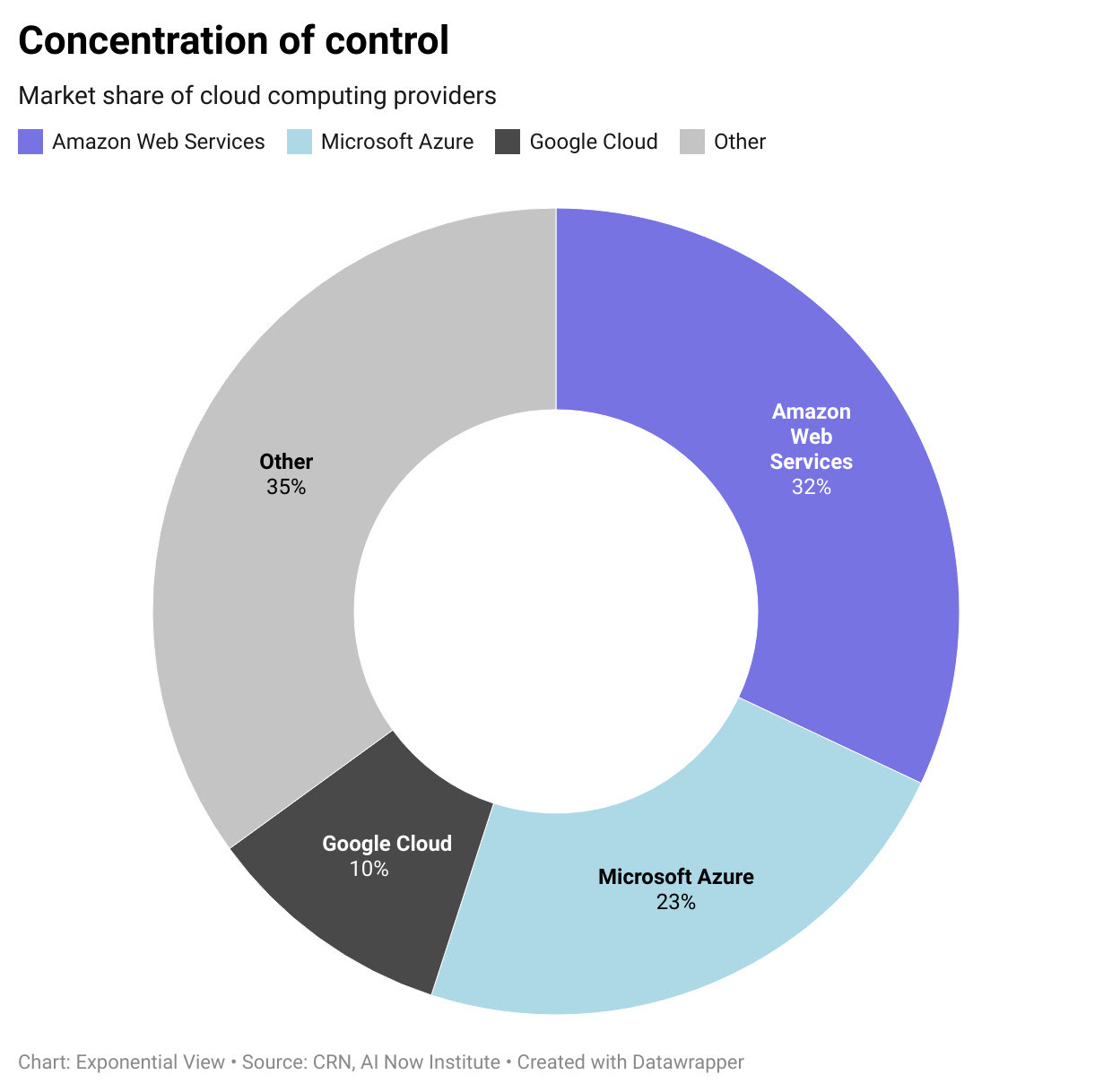

Amid escalating tensions in the tech sphere, the US government is now pondering various measures to restrict Chinese companies' access to American cloud computing services. These measures range in severity, these options include:

Banning US companies from providing cloud computing services to Chinese companies. This would be the most drastic option, and it would likely have a significant impact on the global cloud computing market.

Requiring US companies to obtain a license before providing cloud computing services to Chinese companies. This would allow the US government to vet Chinese companies and to block those that pose a security risk.

Requiring US companies to store data from Chinese companies on servers that are located in the United States. This would make it more difficult for the Chinese government to access this data.

With US companies controlling over 65% of the cloud services market this is a huge point of leverage for the US.

Implementing monitoring systems might involve a multi-tiered approach.

Continuous data flow analysis to detect any anomalous or potentially hazardous operations. Advanced AI algorithms could be deployed to recognize patterns that are inconsistent with routine operations.

Real-time notifications could be integrated, alerting stakeholders of flagged operations immediately.

Automated protocols to block risky AI could be established, wherein high-risk activities could be paused or halted pending manual review.

China's use of US cloud services presents a potentially strategic concern for both nations. In times of escalated geopolitical tensions, the US, serving as the host nation for these cloud services, could technically restrict or cut off access to vital cloud resources for Chinese entities. Such a move would be significant: disabling access to storage, processing capabilities, or other cloud functionalities could severely hamper operations of businesses or even essential services that are reliant on these platforms.

For China, the potential for such disruptions might serve as an impetus to further develop and rely on domestic cloud solutions. By bolstering its indigenous cloud capabilities, China could mitigate risks associated with foreign dependency.