Arms Controls for Advanced AI Chips

The new AI chip restrictions signal a shift toward treating advanced technology as a strategic asset akin to conventional arms, highlighting the evolving nature of geopolitics in the digital age.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is at the forefront of modern technological advancement, influencing not only the technological landscape but also the geopolitics and economic strategies of nations. At the heart of AI lies the semiconductor. Recognizing the dual-use nature of these semiconductors, the United States has become increasingly vigilant about their exports to China, leading to the imposition of successive and escalating restrictions in recent years.

The latest restrictions target the shipment of advanced semiconductors from the U.S. to Chinese data centers. Moreover, companies attempting to evade these rules by rerouting shipments through third countries will now face additional scrutiny, as these nations are brought under U.S. licensing requirements. However, the complexity of this issue goes beyond the restrictions themselves, as it involves a multitude of concerns raised by various stakeholders, ranging from the wide scope of the restrictions to potential repercussions on U.S. tech leadership and global collaborations. This article delves into the key takeaways and implications of these escalating measures and their potential ramifications on the global tech landscape.

As of writing it has been less than 24hrs since the new rules were published, we will continue to monitor the situation and update our views.

Key Takeaways

AI plays a pivotal role in contemporary technology, influencing geopolitical and economic strategies for nations. See our piece from a few weeks ago on AI in Great Power Competition for more information.

The U.S. is increasingly cautious about exporting semiconductors to China, recognizing their dual-use potential in AI and military applications.

In October 2022, the U.S. restricted China's access to sub-14nm equipment and chips, along with prohibiting U.S. entities from supporting semiconductor development in China.

Stakeholders raised concerns about the broad scope of the restrictions, advocating for international consensus, potential harm to U.S. tech leadership, lack of allied controls, and collateral damage to global collaborations.

Yesterday, the Biden administration reinforced these controls by adding specificity to the manufacturing equipment restrictions, targeting shipments of advanced semiconductors to Chinese data centers, including countries that are under arms export controls to the AI chip ban and scrutinizing third-country shipments to China. The expansion of controls aims to prevent China from obtaining critical semiconductor manufacturing equipment and advanced ICs.

The new rules include tiered controls for advanced integrated circuits (ICs), exemptions for consumer chips, and measures to address circumvention. The new restrictions are tighter at the leading edge and prevent leakage while not expanding on lagging edge or consumer technologies.

U.S. export controls aim to limit China's access to advanced technology while avoiding complete cutoff, allowing room for US suppliers in China. However, Chinese companies may still increasingly turn to domestic options for critical technology, aligning with Beijing's strategic objectives.

Arms Controls for Advanced AI Chips

The latest AI chip restrictions, bear a striking resemblance to arms control measures in several aspects. Firstly, they showcase a deepening concern within the U.S. government about the strategic implications of advanced AI capabilities. Just as arms control agreements aim to limit the proliferation of weapons with the potential to disrupt global security, these restrictions target AI capabilities that can significantly impact military decision-making, electronic warfare, and intelligence operations. This demonstrates a growing recognition of AI's role in shaping modern warfare and the need to curtail its spread.

Secondly, the tiered approach introduced in these controls is akin to arms control regimes that categorize weaponry based on their potential threat. By classifying AI chips into different tiers and imposing stricter regulations on the most potent ones, the U.S. is essentially applying a risk-based assessment, mirroring how arms control treaties treat weapons of varying destructive capabilities.

Additionally, the expanding list of countries subject to these controls, particularly the "unfriendly" ones, is reminiscent of arms embargoes. This broader reach reflects a concerted effort to prevent third-party countries from facilitating China's access to advanced AI technology, mirroring the intent behind arms embargoes on rogue nations.

Furthermore, the emphasis on the potential misuse of AI in surveillance systems for human rights violations adds a humanitarian dimension to these controls, aligning them with the ethical considerations often seen in arms control discussions.

Overall, these AI chip restrictions signal a shift toward treating advanced technology as a strategic asset akin to conventional arms, highlighting the evolving nature of geopolitics in the digital age.

The Escalating Measures

October 2022 Restrictions: Last year, the U.S. government made clear moves to limit China's progress in supercomputing and AI by restricting its access to sub-14nm equipment and corresponding chips. This initiative also extended to prohibit U.S. entities from supporting semiconductor development within China's borders.

Public Comments and BIS Responses: Navigating a Complex Landscape

Despite these controls, there have been challenges. Entities like Huawei and SMIC found ways to break through the ‘sub-14nm barriers’, and companies such as Nvidia sought design-around solutions to navigate the tight regulations.

For background information re recommend readers review out previous posts on The Huawei SMIC Breakthrough and The NVidia Design Around.

However, the true complexity emerges from the myriad of concerns raised by stakeholders, ranging from the broad scope of the restrictions to potential threats to U.S. tech leadership. Through the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) responses, it becomes evident that there's a delicate balance at play: addressing national security concerns while acknowledging the integral role of global trade partnerships. Several issues came to light in the latest BIS responses to public comment:

Broad Application Concerns: Some stakeholders felt the October 7 IFR was unnecessarily expansive, preferring established multilateral controls such as the Wassenaar Arrangement. However, BIS argues that the broad scope is crucial to navigate the increasingly intertwined realms of China's commercial and military sectors.

Call for Multilateralism: The unilateral nature of the controls raised eyebrows, with advocates pushing for international consensus. BIS's response hinged on the urgency of national security, necessitating swift and independent action.

The Potential Own-Goal: Concerns about the U.S. potentially sidelining itself from global tech advancements by imposing these controls were raised. BIS countered, emphasizing that the controls aim for security, not supply chain disruption.

Allied Apathy: The noticeable lack of similar controls from U.S. allies was brought up as a potential weak point. BIS highlighted adjustments made to maintain collaboration capacities with these allied countries.

Collateral Damage: Stakeholders raised concerns about potential impediments to global health and environmental collaboration. BIS's licensing policies aim to be lenient where risks are minimal, safeguarding these collaborative endeavors.

The New Rules

October 2023 Restrictions: The Biden administration, just a year after the first round of restrictions, has further reinforced these controls. The fresh restrictions target the heart of China's AI capabilities by curtailing the shipment of advanced semiconductors from the U.S. to Chinese data centers. Companies looking to sidestep these rules by rerouting shipments through third countries would face additional scrutiny, as these nations will now also come under U.S. licensing requirements.

These controls were strategically crafted to address, among other concerns, the PRC’s efforts to obtain semiconductor manufacturing equipment essential to producing advanced integrated circuits needed for the next generation of advanced weapon systems, as well as high-end advanced computing semiconductors necessary to enable the development and production of technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) used in military applications.

Advanced AI capabilities—facilitated by supercomputing, built on advanced semiconductors— present U.S. national security concerns because they can be used to improve the speed and accuracy of military decision making, planning, and logistics. They can also be used for cognitive electronic warfare, radar, signals intelligence, and jamming. These capabilities can also create concerns when they are used to support facial recognition surveillance systems for human rights violations and abuses. Commerce Strengthens Restrictions on Advanced Computing Semiconductors, Semiconductor Manufacturing Equipment, and Supercomputing Items to Countries of Concern

Advanced Computing Chips Rule (AC/S IFR)

Advanced Computing Chips Rule (AC/S IFR) Document

The AC/S IFR retains the stringent PRC-wide licensing requirements imposed in the October 7, 2022, rule and makes two categories of updates:

First, adjusting the parameters that determine whether an advanced computing chip is restricted;

Second, imposing new measures to address risks of circumvention of the controls.

The AC/S Interim Final Rule (IFR) continues the licensing measures from the October 7, 2022 mandate, with a core focus on advanced integrated circuits (ICs) exports, especially those used in datacenter AI. The objective is to prevent possible regulatory sidestepping by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and associated entities. In essence, BIS is refining its controls to be more specific and targeted.

Parameters that determine whether an advanced computing chip is restricted;

Based on public comments, recent technological developments, and analysis of the prior rule’s national security impact, the AC/S IFR removes “interconnect bandwidth” as a parameter for identifying restricted chips. The rule also:

Restricts the export of chips if they exceed either of two parameters:

(1) The preexisting performance threshold set in the October 7 rule; or

(2) A new “performance density threshold,” which is designed to preempt future workarounds.

Requires a notification for the export of certain additional chips with performance just below the restricted threshold. Under new “License Exception Notified Advanced Computing (NAC),” following receipt of notification for exports and reexport to Macau and destinations identified as subject to a U.S. arms embargo (including the PRC), the U.S. government will determine within 25 days whether the transaction may proceed under the license exception or instead require a license.

As part of these updates, we are also introducing an exemption that will permit the export of chips for consumer applications.

This change anticipates potential loopholes where multiple less powerful chips might be combined to match the capacity of restricted ones. To measure a chip's total performance, factors like the 'MacTOPS' rate, the 'bit length of the operation', and the 'applicable die area' are pivotal.

Performance Density Threshold Calculations

The document provides instructions on how to calculate the 'Total processing performance' (TPP) for integrated circuits. The formula for TPP factors in the 'MacTOPS' (the theoretical peak number of Tera operations per second for a specific computation) and the 'bit length of the operation'. A convention is adopted where one multiply-accumulate computation is counted as two operations. The total TPP for an integrated circuit is the sum of the TPPs for each processing unit on it. Finally, 'Performance density' is calculated by dividing the TPP by the 'applicable die area'.

We are sharing these calculations for real world chips with our close contacts and will release more information for free subscribers soon.

The updated regulations for ICs are categorized into two main sections, 3A090.a and 3A090.b, based on their performance metrics. We are calling them Tier 1 and Tier 2 chips for simplicity:

Tier 1 Chips

Classified as Export Control Classification Number ECCN 3A090.a

The IC is regulated if it has a 'total processing performance' of 4800 or more.

Alternatively, it's also regulated if it achieves a 'total processing performance' of 1600 or more, combined with a 'performance density' of 5.92 or more.

Tier 2 Chips

Classified as Export Control Classification Number ECCN 3A090.b

The IC is regulated if its 'total processing performance' is between 2400 and 4800, and its 'performance density' is between 1.6 and 5.92.

Additionally, if the IC has a 'total processing performance' of 1600 or more and its 'performance density' is between 3.2 and 5.92, it will also be under this control.

In summary, these updated parameters broaden the range of controlled ICs compared to the previous October 7 IFR. This expansion aims to regulate even those ICs below the initial thresholds but which can still aid in training advanced military-grade AI.

Consumer Chips Exemption

In recognition of the consumer market's different dynamics, an exemption for chips designed for consumer applications is now in place. This is consequential as it represents a shift toward focusing on critical military technology, not all technology. This keeps open critical streams of revenue for US chip companies.

New measures to address circumvention of controls

Establishes a worldwide licensing requirement for export of controlled chips to any company that is headquartered in any destination subject to a U.S. arms embargo (including the PRC) or Macau, or whose ultimate parent company is headquartered in those countries, to prevent firms from countries of concern from securing controlled chips through their foreign subsidiaries and branches.

Creates new red flags and additional due diligence requirements to help foundries identify restricted chip designs from countries of concern. This will make it easier for foundries to assess whether foreign parties are attempting to circumvent the controls by illicitly fabbing restricted chips.

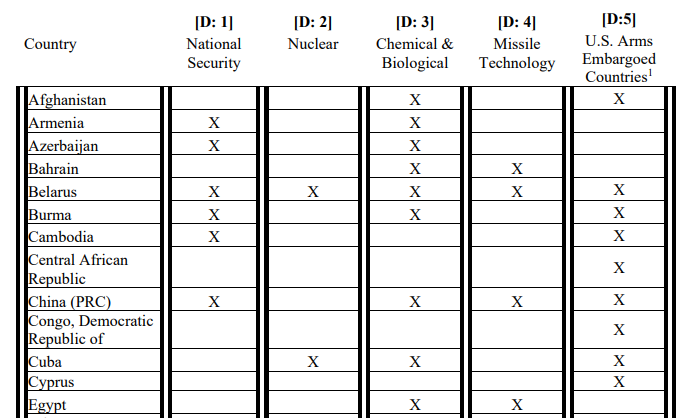

Expands licensing requirements for export of advanced chips, with a presumption of denial, to all 22 countries to which the United States maintains an arms embargo (including the PRC) and Macau.

Imposes license requirements for export of advanced chips, with a presumption of approval, to these same additional countries, in response to reporting that countries of concern have used third countries to divert or access restricted items. This will provide greater visibility for compliance monitoring and enforcement.

Creates a notification requirement for a small number of high-end gaming chips to increase visibility into shipments and prevent their misuse to undermine U.S. national security.

Includes a request for public comments on multiple topics, including risks associated with infrastructure as a service (IaaS) providers, the application of controls on deemed exports and deemed reexports, additional compliance guidance that could be provided to foundries receiving chip designs, and how to more precisely define key terms and parameters in the regulation.

To mitigate indirect PRC acquisitions, the rule expands its oversight to specific country groups. Notably, there's now a monitoring mechanism for select high-end gaming chips to ensure their appropriate use.

BIS had introduced a graded control system based on the potential threat of the ICs. The most potent ICs face stricter licensing requirements, while less potent ones have certain allowances but with conditions attached, especially concerning their destination. Additionally, the U.S. government maintains a close watch on exports of chips hovering just below the restricted performance mark.

Tier 1 Chips banned in ‘Countries of Concern’

To prevent the PRC from acquiring advanced ICs via indirect routes or by accessing datacenters with these ICs, BIS is extending controls of Tier 1 chips to certain countries classified as D:1, D:4, and D:5. This a measure to combat China's use of third-party countries to bypass U.S. export restrictions.

For a comprehensive list of D:1 - D:5 countries refer to the BIS document here. The list generally includes countries subject to arms controls: Afghanistan, Belarus, Burma, Cambodia, Central African Republic, China (PRC), Cuba, Cyprus (now exempt), Iran, Iraq etc.

Tier 2 Chips can be exempt from ban on ‘Countries of Concern’

Items eligible for License Exception Notified Advanced Computing (NAC) are defined as those under Tier 2 (including ICs that are designed or marketed for use in a data center) and specific ICs under Tier 1 (not designed or marketed for use in a data center). These less powerful ICs, which could still be used for training large AI systems, can be exported to places in the D:1, D:4, or D:5 groups. However, if these are exported to Macau or a D:5 country, there must be prior notification.

Mitigating Subsidiary Parallel Imports

The new restrictions expand licensing requirements for export of advanced chips, with a presumption of denial, to all 22 countries to which the United States maintains an arms embargo (including the PRC) and Macau. Creates a notification requirement for a small number of high-end gaming chips to increase visibility into shipments and prevent their misuse to undermine U.S. national security.

Creates new red flags and additional KYC due diligence requirements to help foundries identify restricted chip designs from countries of concern. This will make it easier for foundries to assess whether foreign parties are attempting to circumvent the controls by illicitly fabbing restricted chips.

Imposes license requirements for export of advanced chips, with a presumption of approval, to these same additional countries. This will provide greater visibility for BIS for future compliance monitoring and enforcement.

What to Watch for Next

Preparation for Adaptability: To remain responsive to changing landscapes, licensing requirements for advanced chip exports have been revamped. This ensures that the rules adapt to emerging challenges while preserving national security. Gina Raimondo, the secretary of commerce, said the changes had been made “to ensure that these rules are as effective as possible” and that she expected the rules to be updated at least annually as technology advanced.

Cloud Computing Monitoring: Given the rising importance of cloud computing, the rule calls for public insights. BIS is seeking comments from Infrastructure as a Service (IaaS) providers (Amazon, Google, Microsoft) and other relevant stakeholders about further regulations, especially concerning know your customer KYC requirements that would help in addressing uses that pose national security or foreign policy threats.

Expansion of Export Controls on Semiconductor Manufacturing Items Interim Final Rule (SME IFR)

Export Controls on Semiconductor Manufacturing Items

Key changes made from the October 7, 2022, rule include:

Imposes controls on additional types of semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

Refines and better focuses the U.S. persons restrictions while codifying previously existing agency guidance, to ensure U.S. companies cannot provide support to advanced PRC semiconductor manufacturing while avoiding unintended impacts.

Expanding license requirements for semiconductor manufacturing equipment to apply to additional countries beyond the PRC and Macau, to 21 other countries for which the U.S. maintains an arms embargo.

More Clarity on the Technology Level of Equipment

The Export Control Classification Number (ECCN) for manufacturing equipment have undergone revision by incorporating the term “systems designed for” and removing “systems capable of” to hone in on the controls. The term “systems capable of” was swapped as BIS recognized its potential to unintentionally encompass tools utilized for older generation logic ICs. The choice of “designed for” offers precision in controlling systems dedicated to crafting cutting-edge logic ICs.

For instance, SMIC is able to access DUV – a tool crafted for 14nm but capable of achieving 7nm albeit with compromised yield.

Getting Nitty Gritty with Technical Details of Equipment

BIS has added items under ECCNs 3B001 and 3B002, and associated software and technology for fabricating logic ICs with non-planar transistor architecture or with a production technology node of 16/14 nanometers or less.

Although these items are not yet formally controlled under a multilateral regime, the urgency and criticality of the U.S. national security concerns have motivated unilateral control pending adoption through the Wassenaar Arrangement. BIS have been getting some technical advice because they have added some real specificity to the new restrictions, some examples of the technical details are:

added to control equipment designed for wet chemical processing and having a largest ‘silicon germanium-to-silicon etch selectivity’ ratio of greater than or equal to 100:1.

equipment designed for dry etching, including isotropic dry etching as specified (3B001.c.1.a) and anisotropic dry etching as specified (3B001.c.1.b and c.1.c)

Note 2 is added to inform the public of the types of etching that are included in the scope of 3B001.c.1.b, e.g., etching using RF pulse excited plasma, plasma atomic layer etching, and plasma quasi-atomic layer etching

equipment designed for wet chemical processing and having a largest ‘silicon germanium-to-silicon etch selectivity’ ratio of greater than or equal to 100:1

The items added to 3B001.d.3, d.4, d.5, and d.8 include advanced fabrication equipment designed for metal deposition of the barrier layer, liner layer, seed layer, or cap layer of metal interconnects.

control of equipment designed for ALD or chemical vapor deposition (CVD) of plasma enhanced low fluorine tungsten films. This equipment is critical in filling voids in advanced-node device structures with higher and increasingly narrow aspect ratios, which minimizes resistance and improves performance

Enhanced Visibility into Semiconductor Equipment Distribution

Even if approved, adding a license requirement for destinations in Country Group D:5 (which includes countries such as Afghanistan, Belarus, China, Iraq, Libya, Syria, Russia, and Venezuela) will provide greater visibility into the flow of semiconductor manufacturing equipment, associated development and production technology and software, as well as specially designed parts, components and assemblies therefor to other countries and their intended end uses.

Control Equipment That Makes the Equipment That Makes the Chips

Furthermore, the modifications address systems employed in the creation of other equipment, indicating a layered approach to control. The definition of ECCN 3B001 has been updated from the below to add the text in bold to include equipment that makes the equipment that makes the chips… some nested logic…

3B001 Equipment for the manufacturing of semiconductor devices or materials “and equipment for manufacturing semiconductor manufacturing equipment”

,as follows (see List of Items Controlled) and “specially designed” “components” and “accessories” therefor.

Additions to the Entity List

BIS is adding to the Entity List two PRC entities and their subsidiaries (a total of 13 entities) involved in the development of advanced computing chips that have been found to be engaged in activities contrary to U.S. national security and foreign policy interests. These entities will also be subject to restrictions on foreign-produced items made with U.S. technology.

Foundries producing chips for these listed parties will need a BIS license before the foundries may send such chips to these entities or parties acting on behalf of these entities as a result of applying the “footnote 4” Entity List foreign direct product rule designation.

The entities are Shanghai Biren Intelligent Technology and Moore Threads Technology Co. Biren is a fabless semiconductor design company. The company was founded in 2019 by Lingjie Xu and others, all of whom were previously employed at NVIDIA or Alibaba. Moore Threads specializes in graphics processing unit (GPU) design, established in October 2020 by, Zhang Jianzhong, the former global vice-president of Nvidia and general manager of Nvidia China. This send a clear message that us US aims to contain the ex-NVidia AI chip knowledge in China.

These entities are involved in the development of advanced computing integrated circuits (ICs). As described in an upcoming amendment to regulations regarding advanced computing items and supercomputer and semiconductor end use, advanced computing ICs can be used to provide artificial intelligence capabilities to further development of weapons of mass destruction, advanced weapons systems, and high-tech surveillance applications that create national security concerns. Entity List Additions

Feedback and Fallout

“We are evaluating the impact of the updated export controls on the U.S. semiconductor industry. We recognize the need to protect national security and believe maintaining a healthy U.S. semiconductor industry is an essential component to achieving that goal. Overly broad, unilateral controls risk harming the U.S. semiconductor ecosystem without advancing national security as they encourage overseas customers to look elsewhere. Accordingly, we urge the administration to strengthen coordination with allies to ensure a level playing field for all companies.” SIA Statement on New Export Controls

A Bit of a Bummer for NVidia

Nvidia has been considerably impacted by these changes. The company revealed that their data center revenue, which includes not just AI-enabling chips but other products as well, sees 20-25% of its generation from China. Analysts believe that while the rising global demand for Nvidia chips in the AI sector could provide an opportunity to offset these losses by redirecting to other markets, concerns over the performance constraints on a broader range of Nvidia chips have caused the company's stock price to dip by approximately 5% on a given Tuesday.

Revisions to the "Validated End User" List

In an effort to adapt to the changing landscape, the U.S. Department of Commerce also recently has made adjustments to its "validated end user" list, which specifies the recipients of certain technological exports. This allows giants like Samsung and SK Hynix to continue supplying some U.S. chipmaking tools to their factories in China. I would speculate that installing kill switches on equipment functioning in a Korean fab in China might be incorporated within this new framework.

China’s Grand Plan Faces Challenges

China is making aggressive strides in the technology arena. A plan rolled out by authorities, inclusive of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), aims to amplify China's collective computing power by more than 50% come 2025. The ambitious target is to reach 300 EFLOPS. While this could be feasible, the path to this goal may rely on costly and inefficient technology, lacking the innovative edge of American designs. See our piece from a few weeks ago on AI in Great Power Competition for more information.

Getting the Enemy High on Your Supply

“If you give a man a fish, you feed him for a day. If you teach a man to fish, you feed him for a lifetime.” Applied in reverse. "If you take a mans fish, you starve him for a day. If you take away a man's ability to fish, you starve him for a lifetime."

Or more specifically “If you take a nations commodities, you weaken them for a day. If you take away a nations manufacturing technology, you weaken them for a lifetime.” Zen on Tech, Sept 8th

History is littered with examples of inducing foreign dependence on domestic goods. Today, US policy makers are finally recognizing these dynamics and understanding that broader restrictions incentivize the designing out of US technology in the Chinese supply chain. Chinese AI companies are increasingly limited in their options for sourcing domestically. The strategy appears to be for the U.S. to continue supplying Chinese firms with mid-range technology – good enough to be useful but not advanced enough to threaten U.S. technological leadership. By doing this, if U.S. suppliers provide tech options that are more cost-effective than what's available domestically in China, it creates a dependency, challenging the growth and sustainability of the indigenous supply chain.

With fewer top-tier domestic options like Biren and Moore Threads, Chinese AI firms will continue to be tethered to foreign suppliers. If these U.S. suppliers offer tech that's more cost-effective than what's available from China's indigenous sources, it further undermines the local supply chain, engendering deeper dependencies.

Dr. Doug Fuller of the Copenhagen Business School claims that Chinese semiconductor equipment firms have increased their share of China’s domestic market from 8.5 percent in 2020 to 25 percent in the first 10 months of 2022, though these sales were overwhelmingly concentrated at legacy nodes and far from the state of the art. In Chip Race, China Gives Huawei the Steering Wheel: Huawei’s New Smartphone and the Future of Semiconductor Export Controls

Since 2018, U.S. policies have made it challenging for China to fully realize its tech ambitions. While the U.S. has imposed severe costs, pushing China towards self-reliance in semiconductors, it hasn't yet pulled the plug entirely. The Huawei saga is a testament to this. First, the U.S. allowed Huawei to stock up on American chips before implementing restrictions. Then, there was a leeway given to Chinese firms to accumulate equipment from the U.S., Netherlands, and Japan, before broader sales restrictions came into effect. Even with these restrictions in place, China continues to acquire key technology and expertise.

In essence, the lessons from history remain relevant. By controlling the supply of essential commodities or technologies, it's possible to create dependencies that can be leveraged for strategic advantage. However, given Beijing’s strategic awareness of this dynamic, we anticipate that Beijing will force Chinese AI and infrastructure companies to purchase domestic options.