China Chip Glut and Cloud Competition

The rapid buildup of chip production capabilities over the past few years, now brings the challenge of finding a market for the increased output

Greetings from New Zealand! For the next few weeks, I'll be here, engaged in some interesting projects focused on expanding manufacturing capabilities and incorporating AI into industrial control systems. Given the demanding nature of this work, please bear with me as the commentary in this edition is a bit lighter than usual. However, I'm excited about the analysis we’re gathering, which I look forward to sharing in detailed write-ups soon.

If you haven’t already, take a look at our piece last week that puts the strategic technology competition into context:

Chipping Away At China’s AI

Losing out on AI will be a national strategic failure for a great power. Technological phase changes are opportunities for ascending entities to overtake established ones, AI is one such example. In this analysis we describe how the new export controls effect the dynamic of technology competition. While the new controls have been a boon for China’s dome…

The Big Glut in Chip Production

Zhao Haijun, the co-chief executive of SMIC, recently highlighted a significant shift in the global semiconductor landscape. He pointed out that "geopolitical factors" are leading to the duplication of supply chains and construction efforts in the industry. This shouldn’t come as a surprise to folks in the industry. This situation, as Zhao noted, results from a rapid buildup of production capabilities over the past few years, now facing the challenge of finding a market for the increased output.

Zhao Haijun, SMIC’s co- chief executive, said on Friday that “geopolitical factors” were causing “duplication of construction and supply chains”.

“From a global perspective, there will be excess production capacity,” he said, “and it will take a lot of time to slowly digest the production that has been built hastily in recent years.” Financial Times

This observation aligns with recent developments in the Chinese semiconductor sector. Before recent bans, Chinese chip equipment companies had little incentive to innovate or develop cutting edge technologies. They operated in a market that was efficiently catered to by foreign firms, with no strategic compulsion to excel in the domain. However, the imposition of bans changed this dynamic.

From April to September, there was a conspicuous surge in Chinese imports of chip-making equipment. From a modest figure of $1.5M in April, imports climbed steeply to an impressive nearly $4M by September. This sudden spike has undeniably boosted businesses in the US, Japan, and the Netherlands, where major semiconductor capital equipment manufacturers are based. Chinese fabs, eager to secure equipment ahead of bans, have been on a buying spree, accumulating significant volumes of foreign chip-making equipment.

Yet, this influx of foreign machinery might be a double-edged sword for China's semiconductor ambitions. While Chinese firms are stocking up on foreign tech, they could inadvertently be closing the doors on their domestic chip equipment manufacturers. The longevity of chip-making equipment, which can be operational for up to 15 years, means that once a chip manufacturing facility is equipped, there is little room for replacements or additions for many years.

The ideal scenario for countries like the US would be for China to become heavily reliant on foreign chip making technology. This would not only assure consistent demand from China for many years but would also stifle the growth of potential competitors in China's domestic market. For burgeoning Chinese equipment makers, this presents a daunting challenge. The road to matching global leaders in semiconductor machinery is already steeped in complex technical challenges. If domestic sales opportunities diminish, these firms will struggle to gather critical operational data needed to refine and optimize their machines.

China Falling Further Behind on Datacenter Scale

The United States currently holds a leading position in the global hyperscale data center market, hosting over half of the world’s capacity in this sector. Out of more than 800 major data centers worldwide, 53% are located in the U.S. Europe accounts for 16%, China for 15%, and the rest of the world makes up the remaining 16%.

AI winter in China: In the context of China's tech industry, there's a notable divergence in the fortunes of different sectors. While China's large-scale tech companies, or Hyperscalers, have been navigating through restrictions effectively, leveraging scale and inventory, the country's AI startups have been struggling. A significant portion of the funding for AI startups, sometimes up to 80%, is typically allocated to computing resources. The restrictions on American chip technology have severely impacted venture capital investments in China's AI sector. From a high of $30 billion in 2018, AI venture capital in China has plummeted to just $2 billion in 2023. In contrast, the U.S. reached its peak AI venture capital investment of $120 billion in 2021, which has since reduced to $50 billion in 2023.

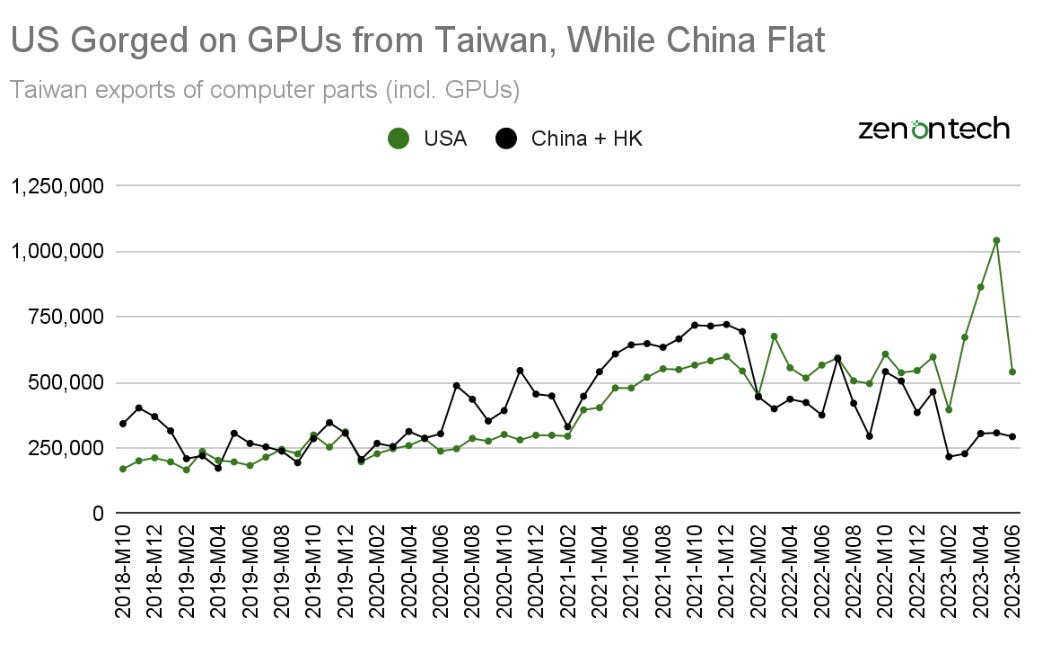

GPU boom in the US: Even though some Nvidia chips remain accessible to China, the country is still trailing behind the US in scale. Data on Taiwan’s exports of computer parts, including GPUs, highlights this disparity. While the U.S. has seen a substantial increase in Taiwanese computer parts imports – up 50% year-over-year in April and 100% in May – exports from Taiwan to China have decreased by 30% year-over-year in these same months.

China chips good, tech bad: This trend underscores the broader impact of U.S. technology restrictions on China. These bans have compelled Beijing to redirect significant resources towards its semiconductor industry. This shift, however, has had the unintended consequence of depriving the burgeoning AI sector of critical investments and resources in the short term.

Global cloud services growing: Global spending on cloud infrastructure services reached over $68 billion in Q3, marking an 18% year-on-year increase and a $10.5 billion growth from the same quarter last year. This surge represents the fifth consecutive quarter of significant growth in the cloud market. Despite economic and political challenges, generative AI technology is playing a key role in driving this expansion. The quarter-on-quarter growth was notably high at 5%, the most substantial since 2021, excluding typical Q4 peaks.

Cloud services are an important leverage point to keep open to China: While the U.S. is considering limiting China's access to American cloud computing services, a complete ban would be counter productive due to the strategic advantage it offers. U.S. cloud services, particularly those using high-end GPUs not available in China, could give Chinese IT and AI companies using them a competitive edge over local firms while increasing reliance on US services. Consequently, Beijing will need to focus on enhancing its domestic cloud infrastructure to mitigate reliance on foreign providers, balancing technological progress with strategic security.