The 'Next China' Doesn't Exist

While FDI is gradually moving away from China, "Factory Asia" remains the backbone of global export potential. Though there is no equivalent to China’s vast manufacturing hub, there are alternatives.

The "China Shock" has redefined global manufacturing over the past two decades. China’s strategic investments in infrastructure, technology, and education—alongside its vast, low-cost workforce and a tightly controlled business environment—have transformed it into the world’s manufacturing powerhouse. This centralised ecosystem drew in production from Southeast Asia and beyond, creating a colossal manufacturing surplus and positioning China as the beating heart of global supply chains.

However, recent shifts show that multinational companies are increasingly diversifying their production bases away from China. This trend, while significant, doesn’t spell the end of China’s role in global manufacturing. While There Is No Equivalent, there are Alternatives. Although viable options are emerging, no single country offers the scale, efficiency, and integrated infrastructure that China does. For years, China has been a remarkable, centralised solution for the world’s manufacturing needs, but now companies must adapt to a more fragmented landscape. This requires a refined approach to international relations and a nuanced strategy for supply chain diversification.

As this new era of globalisation unfolds, multinationals are tasked with balancing China’s enduring advantages against geopolitical risks and rising costs. The challenge of managing multiple production centres across different regions signals a shift from the efficiencies of centralisation to the complexities of resilience—a transformation that will likely redefine the global manufacturing landscape.

By now, China’s property collapse and its strategic pivot into tech manufacturing and electric vehicles have been extensively covered in the media. But in this piece, I bring the perspective of a technologist and manufacturer—someone immersed in the realities of manufacturing and investment decisions—to the conversation.

Disclaimer: This is economic analysis from a tech and manufacturing guy; viewer discretion advised. This piece has been sitting untouched in my drafts for months because I’ve been super busy. Some of the research might be slightly stale, but I believe there’s still valuable insight here for readers. I hope you enjoy.

Key Takeaway

In the shifting landscape of global manufacturing, while FDI is gradually moving away from China, "Factory Asia" remains the undisputed backbone of global export potential. Regions like Saudi Arabia, Mexico, and Eastern Europe are rising as specialised hubs—Saudi as a future regional powerhouse, Mexico as the cost-effective supplier to the US, and Eastern Europe as Europe’s industrial engine. However, the intricate supply chains of Asia, honed over decades, are challenging to replicate or compete with on a global scale.

That said, these advantages don’t come without risks. Vietnam, a rising star in manufacturing, is better integrated into "Factory Asia," benefiting from its access to raw materials and established supply chains. With so much FDI from China, Vietnam is essentially diversification with Chinese characteristics, enabling it to attract global investment while gaining benefits from the regional economic powerhouse. However, Vietnam’s position in the South China Sea exposes it to geopolitical vulnerabilities. While Vietnam itself is unlikely to face sanctions, a Pacific conflict could severely disrupt maritime trade, effectively isolating its supply chains. Ho Chi Minh City, located further south, offers the lowest risk for Western companies aiming to minimise potential disruptions, but no location in the region is entirely risk-free.

In the end, while India and other emerging markets have their strengths, Vietnam remains the more competitive manufacturing option due to its connectivity to Asia’s established supply networks. Its lower-cost structure and strategic access to inputs make it a natural fit for investors seeking reliable export channels—albeit with the caveat of geographic and political exposure. As global manufacturing evolves, businesses will need to balance these emerging centres with the enduring strength and complexities of Factory Asia.

China Shock and The Surplus Problem

The Chinese government's strategic investments in infrastructure, education, and technology, coupled with its large labor force, suppressed labor rights and favorable business environment, have enabled the country to attract a significant portion of the world's manufacturing surplus. China's surplus has played a crucial role in driving the relocation of manufacturing from Southeast Asia to China. As foreign companies sought to capitalize on China's labor pool they began to shift their production lines from their home countries as well as from countries like South Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong to China. This influx of foreign investment helped to fuel China's rapid industrialization and economic growth, transforming the country into the world's manufacturing hub. This investment led to huge manufacturing surpluses, now a point of contention.

Germany's Wage Suppression and its Impact on Mediterranean Manufacturing

A useful example of the effect of policies aimed at creating large manufacturing surpluses is evident in Germany and the Eurozone in the past two decades.

Starting in the early 2000s, Germany implemented labor reforms, including the "Agenda 2010" reforms, which made the labor market more flexible but also led to suppressed wage growth. This strategy allowed Germany to maintain competitive labor costs, making its exports cheaper compared to those of countries with higher wage growth.

The impact of Germany's wage suppression was felt across the Mediterranean region, where manufacturers in Greece, Italy, and Spain struggled to compete with German products. As German goods became more attractive in the domestic market and across Europe, local manufacturing sectors in these countries found it increasingly difficult to compete. This contributed to a deindustrialization effect in some sectors of these economies.

Germany's economic policies also led to significant trade surpluses, resulting in the country exporting far more than it imported. This imbalance had a disproportionate impact on Mediterranean countries, which often ran trade deficits with Germany. The common Euro currency meant that Mediterranean countries could not devalue their currency to make their exports cheaper and imports more expensive, a traditional method to correct trade imbalances. The strict fiscal austerity measures imposed as part of bailout agreements during the Eurozone crisis further squeezed these economies, reducing domestic demand and investment in manufacturing sectors.

The situation has led to criticisms of Germany's role in the economic challenges faced by Mediterranean countries, particularly concerning manufacturing and wage growth. The complexities of economic integration within the Eurozone, where differing national policies can have wide-reaching impacts across the union, are highlighted by this situation.

The Global Economy: A Tale of Two Strategies

Both Germany and China have utilized economic strategies that prioritize national interests and competitiveness, often at the expense of other economies. Germany's wage suppression within the Eurozone has contributed to economic disparities that challenge the cohesion of the EU's single market. In contrast, China's trade surpluses with the U.S. have raised issues about global economic fairness, prompting shifts in global supply chains and trade policies.

The effects on Spain and the U.S. highlight a critical aspect of international economics: the delicate balance between national strategies and their international impacts. For Spain, economic recovery and growth may hinge on the ability to innovate beyond traditional industries and possibly re-negotiate EU economic policies that constrain fiscal and monetary flexibility. For the U.S., addressing trade imbalances with China involves not only negotiating trade terms but also enhancing domestic capabilities in technology and manufacturing.

The China-US trade imbalance has had significant implications for the US economy, including a decline in the manufacturing sector. To address the imbalance, the US is implementing policies focused on increasing its competitiveness in the global market to retain and grow value added manufacturing, while diversifying imports of low value added products.

China: From Property to Industrials

While protectionist actions were already kicking off with Donald Trump in 2016, since 2020, Beijing has doubled down on support for the manufacturing sector. Beijing got ahead of the ‘investor riot’ of 2022.

China's economic landscape is undergoing a significant transformation as the country pivots away from its reliance on property and infrastructure development toward manufacturing technology. This shift is driven by the need to rebalance the economy and address the challenges posed by a slowing growth rate. However, this transformation comes with its own set of challenges and implications for the Chinese economy.

This is probably one of the most important charts right now about the Chinese economy. To offset the collapse in the real estate sector, Beijing has managed to surge credit to the manufacturing sector, which has helped prevent a total collapse of domestic credit growth and demand Shanghai Macro Strategist, X account

Bloomberg: Banks Are Roaring Back in Xi’s New China

The Problem with Doubling Down, The World is Satisfied

While change in investment in 2020 was a possible way to saving Chinese banks from failing property sector, it will create knock on effects for global manufacturing and trade dynamic. It adds fuel to the fire of cheap Chinese manufacturing and provides yet more fodder for targeted anti-China political blocs and protectionist moves.

While China accounts for 18 percent of global GDP and only 13 percent of global consumption, it currently accounts for an extraordinary 31 percent of global manufacturing. If China maintained annual GDP growth rates of 4–5 percent while also maintaining the role of manufacturing in its economy, its share of global GDP would rise by less than 3 percentage points in a decade, to 21 percent, even as its share of global manufacturing would rise by more than 5 percentage points, to 36 percent. What’s more, if—as a result of the massive shift in investment from the property sector to the manufacturing sector—the GDP share of China’s manufacturing sector rose above its current 28 percent to, say, 30 percent, China’s share of global manufacturing would rise to 39 percent.

To accommodate this and prevent a global overproduction crisis, the rest of the world would have to allow its manufacturing share of GDP to drop between 0.5 and 1.0 percentage points. It would also have to allow a surge in China’s trade surplus—currently equal to nearly 1 percent of the GDP of the rest of the world—as a 5–8-percentage-point increase in China’s share of global manufacturing would be backed by a 2-percentage-point increase in China’s share of global consumption. What Will It Take for China’s GDP to Grow at 4–5 Percent Over the Next Decade?, Michael Pettis

… The arithmetic, however, is quite straightforward: unless the rest of the world is willing to reverse its strategic economic priorities to accommodate Chinese growth ambitions, global constraints imply that China cannot continue growing its share of global GDP without sharply reducing the growth rate of investment and manufacturing. The only way to reduce these without a sharp drop in GDP growth would be through a sharp rise in consumption growth. That, in turn, would require a reversal of the past direction of transfers, with the only sector capable of funding these transfers being the government.

But that must result in a sharp change in the roles of Beijing and local governments in the Chinese economy. This change would be difficult. In the days of rapid growth, when income was transferred from households to subsidize preferred sectors of the economy, the main political issue was one of deciding who the winners among businesses and governments would be. Now that rebalancing requires that income be transferred back to the household sector, the political issue is one of deciding who the losers are going to be among those same sectors. Picking winners is much less disruptive than picking losers, and it requires either a transformation in the structure of government or—as has been the case in most other countries that have faced this problem—an acceptance of much lower growth rates.

Protectionism Reaction

In recent years, the global economic landscape has witnessed a significant shift toward protectionist policies, driven largely by China's aggressive subsidization of its manufacturing sector. This strategy has not only disrupted traditional trade dynamics but has also sparked a series of retaliatory measures and trade disputes across the globe. This article explores the multifaceted impact of China's subsidization policies, focusing on the resulting protectionism and the global response. Here are some pertinent examples:

US Tariffs on Chinese EV are Purely Symbolic

One of the most significant retaliatory measures has been the United States' decision to quadruple tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs). This move, as reported by the Wall Street Journal, aims to counteract the competitive edge gained by Chinese manufacturers through state subsidies. The tariffs are intended to level the playing field for American EV manufacturers, who have been struggling to compete with the lower-priced Chinese alternatives. Chinese EV’s however have an extremely low market share in the US.

It is commonly agreed that the Biden administration’s recently announced 100% tariff on Chinese made electric cars is entirely symbolic. Already impeded by a 25% tariff, China automobile makers have sold very few electric vehicles in the United States. The purpose of the announcement was the announcement. This is an election year, Michigan is a key swing state, and even though it has no actual impact, the tariff announcement gave President Joe Biden an opportunity to say that he wants to see cars made in America, and by union workers.

Yet while it will have no impact on sales of Chinese electric vehicles to the United States, the decision does draw attention to the widening battle between the United States and China for supremacy in advanced manufacturing. The Biden administration now offers vast subsidies to advanced manufacturing, replicating those offered by Chinese provincial governments. It denies China advanced semiconductors and the equipment to make them, with the intent of hindering China’s advance in technologies such as artificial intelligence models, which use advanced chips. Whether EVs or solar panels, protectionism has the same distorting effect

Australia is Buying Cars from Whoever Sells them Cheap

The Australian government has so far not followed the lead of the US in introducing tariffs, largely because Australia no longer has an automotive industry to protect.

But the international backlash has not escaped the attention of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, which said it will "encourage cooperative avenues to manage these issues, in a manner consistent with international trade rules".

"Australia is committed to maintaining a level playing field for our manufacturers and producers by supporting a robust multilateral rules-based trading system," a spokesperson said.

When asked whether Australia would consider introducing tariffs, the department said decisions on trade policy matters were "made in Australia's national interest".

The FCAI said it supported competition "including an increased presence of Chinese-produced vehicles, that will ultimately benefit Australian consumers". While the US and EU are putting up barriers to Chinese cars, Australians are buying them at record levels

Saudi Deal Failure

China's ambitious plans to expand its influence through trade agreements have also faced significant setbacks. According to Reuters, negotiations for a free trade agreement between China and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) have stalled, largely due to Saudi Arabia's industrial agenda. The failure of these talks highlights the challenges China faces in securing favorable trade deals amid growing global skepticism of its trade practices.

Saudi Arabia's reluctance to move forward with the deal reflects broader concerns about China's economic strategies. Many countries are wary of becoming overly dependent on Chinese trade and investment, fearing that it could undermine their own industrial and economic policies. This impasse is indicative of the growing resistance to China's economic dominance and the protective measures countries are willing to adopt to safeguard their interests.

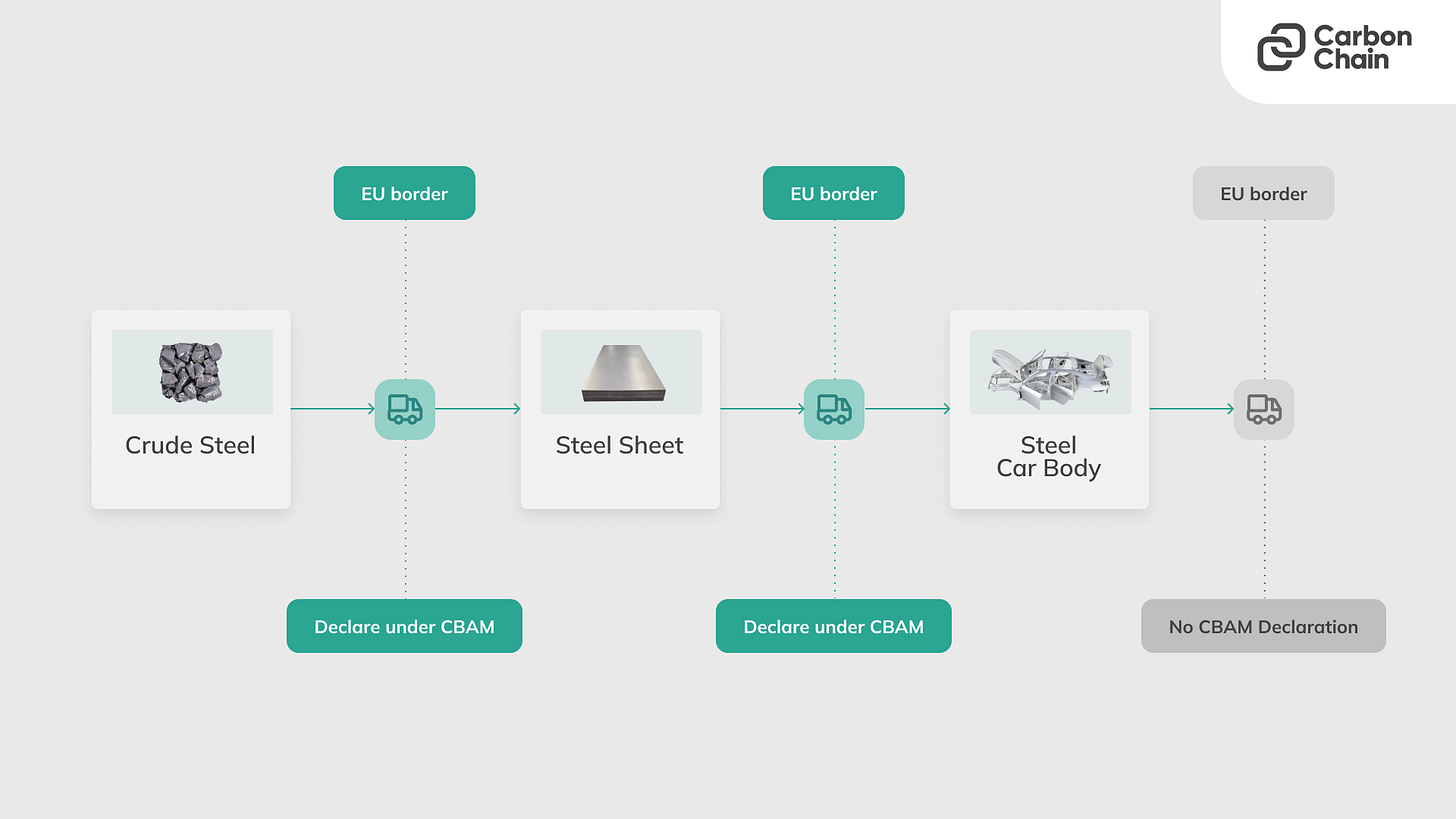

CBAM, Increases Material not Product Import Tariffs.

The European Union has also responded to China's subsidization practices with its own set of protective measures. The introduction of the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is a clear attempt to address the competitive disadvantage faced by European manufacturers due to China's lower environmental standards. By imposing tariffs on imports based on their carbon footprint, the EU aims to level the playing field and promote sustainable manufacturing practices.

CBAM covers a wide range of products, namely: iron and steel, cement, fertilizers, aluminium, electricity and hydrogen, as well as certain goods incorporated in their production. You can see why CBAM isn’t being applied to end products, because it would take a PhD per product to determine carbon consumed and embodied in production. But without CBAM for end products, this is an awesome way to increase the cost of raw materials for European manufacturers.

EU importers of goods covered by CBAM will register with national authorities where they can also buy CBAM certificates. The price of the certificates will be calculated depending on the weekly average auction price of EU ETS allowances expressed in €/tonne of CO2 emitted.

EU importers will declare the emissions embedded in their imports and surrender the corresponding number of certificates each year.

If importers can prove that a carbon price has already been paid during the production of the imported goods, the corresponding amount can be deducted.

In addition to CBAM, the EU has implemented specific protections for its EV industry. These measures include subsidies for European EV manufacturers and stricter regulations on imported EVs, aimed at boosting the competitiveness of local producers. The EU's approach reflects a growing trend of regional protectionism, where economic blocs seek to shield their industries from external competition through regulatory and fiscal measures.

Manufacturing Hot Spot No More

A perfect storm of factors has created an unfavorable environment for manufacturing in China. Tariffs, investment restrictions, and the challenges of operating in an increasingly authoritarian country have all contributed to a decline in foreign investment and technology transfer. Rising wages and a less business-friendly environment have also taken a toll. Meanwhile, the rest of the world, particularly the US, is accelerating its development of data center capacity and AI capabilities. As a result, Chinese businesses are struggling to find niches where they can succeed.

High Wages

The rising cost of labor in China has become a significant concern for foreign investors. With wages in China increasing by as much as 2-3 times compared to South Asian countries, the cost of production is escalating. This shift in labor costs has made China a less attractive destination for foreign companies, particularly those in labor-intensive industries. As a result, many manufacturers are reevaluating their supply chain strategies and exploring alternative locations with lower labor costs. This trend is likely to continue, as China's labor market continues to tighten, driven by a rapidly aging population and increasing labor costs. As a consequence, companies are being forced to adapt to this new reality, seeking out more cost-effective manufacturing destinations to maintain their competitive edge in the global market.

FDI and Trade Collapse Signals Shift in Global Manufacturing Landscape

The recent collapse in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in China is a stark indication that foreign businesses are no longer willing to invest in the world's second-largest economy. Gone are the days when companies would flock to China to set up new factories, invest in new plant and capital equipment. Instead, foreign companies are now opting for alternative manufacturing destinations, driven by a cocktail of perceived geopolitical risks, trade tensions, and regulatory uncertainties.

To get a gut feel of the impact consider that while FDI has cratered -110% to below zero, if we take a guess that on average that FDI goes into assets with a 5-year life (some will be taken up by services and some by longer life assets, but lets use 5-years) then the capital equipment that was established through FDI has only declined 10% and would take another 5 years to depreciate to zero.

The shift is largely attributed to the growing concerns over geopolitical risks, including the risk of sanctions and war. Rather than shutting down existing operations in China, companies are choosing to let their factories depreciate while setting up new facilities elsewhere. This strategic move is a clear indication that foreign businesses are no longer willing to take on the perceived risks associated with operating in China. Washingtons trade policies, including tariffs and trade restrictions, have further exacerbated the situation, making it increasingly challenging for foreign companies to operate in China.

The implications of this shift are far-reaching, with significant consequences for the global manufacturing landscape. As foreign companies diversify their manufacturing operations, new markets and destinations are likely to emerge as attractive alternatives. This could lead to a reconfiguration of global supply chains, with companies seeking out more stable and predictable environments in which to operate.

The sudden decline in foreign direct investment (FDI) in China serves as a stark reminder for policymakers and business leaders to re-examine the intricate relationships between geopolitics, trade, and investment. While a war or further escalation can be avoided, it is plausible that FDI in China will rebound as Beijing continues to woo foreign businesses and invests in maintaining existing production capacity in China. This presents an opportunity for China to revitalize its economy and reassert its position as a global investment hub.

IP Creation Still Limited in China

The shift away from China coincides with an era where the country is increasingly reliant on imported intellectual property (IP). Despite the attention-grabbing headlines in Chinas development, China continues to face a significant shortfall in IP trade. For historical context, consider Japan before the Asian crisis in 1997, when its population was still growing at a rate of 0.2% per year; it faced an IP trade deficit of just over $3 billion in current USD. In contrast, China, now experiencing zero population growth, grapples with an IP trade deficit exceeding $30 billion USD. This is further compounded by the decline in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and an aging population, intensifying China's reliance on foreign IP. These factors together pose substantial hurdles for the development of Chinese technology, signaling potentially profound challenges ahead for its innovation landscape.

Key Ingredients for a Production Hub

When searching for manufacturing alternatives, it is crucial to pay close attention to countries that implement policies that suppress wages and labor rights to make exports more competitive. These policies, often referred to as "beggar-thy-neighbor" strategies, can have far-reaching consequences for the global economy and the workers who are affected. By identifying countries that engage in these practices, investors and businesses can make informed decisions about where to establish or expand their operations. For instance, Germany's wage suppression policies have contributed to a significant trade surplus, while China's state-led industrial policies have driven its economic growth. Similarly, countries like Vietnam and Cambodia have implemented policies to attract foreign investment by offering low wages and lax labor regulations. By monitoring these policies, businesses can assess the potential risks and benefits of investing in these countries and make informed decisions about their global supply chain strategies.

Assessing Favorable Business Environments

Evaluating development indices such as the Corruption Perceptions Index, Global Innovation Index, EF English Proficiency Index, and Economic Complexity Index alone cannot fully determine the optimal location for manufacturing. While these indices provide valuable insights into various aspects of a country’s environment, the decision ultimately hinges on the ease of operating within the country and the robustness of its local tech environment and supporting industries.

Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is an index that ranks countries "by their perceived levels of public sector corruption, as determined by expert assessments and opinion surveys." The CPI generally defines corruption as an "abuse of entrusted power for private gain". The index is published annually by the non-governmental organization Transparency International since 1995. https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2023/

The Global Innovation Index is an annual ranking of countries by their capacity for, and success in, innovation, published by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). The index is computed by taking a simple average of the scores in two sub-indices, the Innovation Input Index and Innovation Output Index. https://www.wipo.int/global_innovation_index/en/2023/

EF English Proficiency Index (EF EPI) attempts to rank countries by the equity of English language skills amongst those adults who took the EF test. https://www.ef.com/wwen/epi/

Economic Complexity Index (ECI) from Harvard Growth Lab’s Country Rankings assess the current state of a country’s productive knowledge. Countries improve their ECI by increasing the number and complexity of the products they successfully export. https://atlas.cid.harvard.edu/rankings

Ability to Manufacture and Export

A robust manufacturing sector, measured by its contribution to GDP and exports, is a hallmark of a favorable business environment and effective policies. Vietnam stands out as the only emerging market that has consistently grown its manufacturing sector over the past decade. In contrast, India's manufacturing sector remains underwhelming. Interestingly, many Asian countries have a significant portion of manufacturing as a percentage of their GDP, highlighting the diversity of manufacturing landscapes in the region.

Vietnam: Diversification with Chinese Characteristics

Vietnam has emerged as a standout in the manufacturing sector, with a proven track record of success and export market share growth over the past decade. The country's geographic proximity to China and pragmatic one-party leadership have contributed to its success. However, Vietnam's economy faces long-term challenges, including its reliance on exports and a worrying debt trajectory.

The country's unique position in a multipolar world has allowed it to profit from its geographic location. However, Vietnam's economic growth is also vulnerable to disruptions in global trade, particularly in the event of a conflict in the Pacific. The country's government has been consolidating power, which could lead to tighter control over the economy and private sector. Despite these challenges, Vietnam remains an attractive destination for foreign direct investment, with a surge in FDI from China and other Asian countries.

Currency controls: Vietnam's currency management has been characterized by a mix of flexibility and control. The State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) has implemented a managed float regime, allowing the dong to fluctuate within a narrow band. This approach has helped to maintain stability and confidence in the currency, while also allowing for some flexibility in responding to external shocks. The SBV has also implemented various measures to manage capital flows and prevent excessive volatility in the foreign exchange market. While these measures have helped to maintain stability, they have also been criticized for limiting the ability of Vietnamese companies to access foreign capital and invest abroad.

Open to Indian trade: Vietnam's export-oriented economy benefits from a significant advantage: low tariffs for exporting to India. In contrast, India has implemented a 30% tariff on most foreign products to protect its local industries. However, ASEAN has negotiated a trade agreement that has reduced tariffs on many goods to 5% or 0% in recent years, including Vietnamese exports. This favorable trade environment has made Vietnam an attractive destination for exporters. India still maintains high tariffs on Chinese exports.

Chinese foreign direct investments (FDI) are often funneled through Singapore and reclassified as Singaporean. This allows Chinese companies to circumvent various international regulatory restrictions and tariffs, leveraging Singapore’s favorable investment treaties and robust legal framework. This reclassification facilitates Chinese access to markets that might otherwise be restricted, which has led to geopolitical tensions, particularly with the United States. The U.S. views this as undermining its regulatory efforts and enabling China’s economic strategies, giving Chinese firms an unfair competitive advantage and enhancing China's strategic influence. This dynamic highlights the complex and sometimes contentious role Singapore plays in the global economic landscape.

India

The Indian government faces a unique challenge that sets it apart from the Vietnamese government: Elections. The Indian government needs to balance the demands of various stakeholders, of the 2024 general election. This electoral imperative makes it difficult for the Modi administration to implement reforms that might be unpopular with certain segments of the population, such as economic reforms, wage suppression, and lax labor rights.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Zen on Tech to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.